My last reading roundup covered two years. That's way too long. This time, let's cover the readings of the past seven months or so, everything since the last post.

Before I get started with the visual readings, I have two podcast recommendations. Both can be found at The Anti-Empire Project, hosted by Justin Podur. The first is the Civilizations series, which Podur co-hosts with his former high school history teacher Dave Power. They conceive of the project as an anti-imperialist attempt at a Intro to Western Civilization course. Podur and Power do not come from the exact same place, politically, but they are both interested in providing a thorough, critical, factual, and anti-imperialist history. I have learned so much along the way, and frankly I think I need to go back and re-listen for better retention. Podur and Power are now nineteen episodes deep into their subseries on the scramble for Africa, and I think they've just gotten better and better at teaching this material.

The second podcast recommendation is Anti-Empire Radio, in which Podur hosts conversations about current events with journalists and other knowledgeable people on the anti-imperialist left. I think this show's the best source for anti-imperialist news and analysis, and I tend to consult it to inform my understanding of any issue I can. My own views and Podur's do not align in every possible way, but I haven't seen anyone else do this intellectual work so consistently, and I'd feel pretty lost without his shows.

Onto the readings.

The God of Small Things - Arundhati Roy

A beautiful novel. Takes seriously the task of grounding its story in a real, complex setting, so that the interconnections between gendered violence, economic exploitation, violence against children, racial oppression, and political power become clear while still allowing events to unfold in naturalistic ways. Roy creates a vivid, lush setting so that every event is a result of the life on the page, and nothing feels like an author's contrivance in order to make a point. She makes clear a world filled with constant violence, and yet one where each instance is unique in its pain and its meaning, and where people find love where they can.

I Hope We Choose Love - Kai Cheng Thom

Stand-out essays are "Righteous Callings", "Stop Letting Trans Girls Kill Ourselves", and "Rediscovering Identity at My Grandfather's Funeral". I didn't totally adore this book, but I always appreciate Thom's perspective. Would definitely recommend to anyone in the throes of 'queer community' burnout.

Jailbreak out of History - Butch Lee

The world lost a great thinker in Butch Lee last year. Luckily, we still have her works. This book is composed of two long essays, "The Re-Biography of Harriet Tubman", and "'The Evil of Female Loaferism'". Lee was an Amazon theorist, a militant proletarian feminist, and in this book she brings that lens to the history of New Afrikan women, Black women's resistance in the USA. Lee did not make herself a public figure, but you get the impression that she is a working-class white settler deeply invested in forming radical alliances to overthrow this miserable system.

This book is uncompromising in its accessibility. It could be used to teach people as young as twelve, while being fascinating enough that anyone could learn a lot from it. It is written in the style of the radical pamphlet, and I'd love to spread it as widely. "The Re-Biography of Harriet Tubman" totally re-frames your understanding of Tubman, making it clear that she was a warrior who bravely led a war for the liberation of her people. I think about Harriet Tubman often now. "'The Evil of Female Loaferism'" is an account of the ways that, after the US civil war, those in power did everything they could to re-enslave Black women, and the ceaseless resistance that Black women put up in return. This book gets my heartiest recommendation of this roundup, and you can order directly from the publisher here, if you like.

Common Ground in a Liquid City - Matt Hern

I don't know much about urbanism, and I don't know much about the place(s) that Hern talks about in this book. This was just the beginnings of my studies into both. I thought it was alright, and I appreciated the seeds he's planted for my further research.

"Cause and Effect" from An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding - David Hume

From what I've heard, this book caused a huge stir in european philosophy, and philosophers spent the next several decades finding ways to move forward in light of Hume's critique, especially when it comes to the matter of cause and effect. I read this chapter on the marxist internet archive. The full book is available for free on Gutenberg, but I haven't read it yet, because this kind of academic philosophy is pretty difficult for me.

Hume's argument here, as I understand it, is that our knowledge of cause and effect does not come from pure reason or logic. He does not posit any other source of our understanding, but he provides some pretty compelling arguments as to why it is not our capacity for reason that gives us this knowledge. And since it isn't reason itself, Hume seems honest about the fact that his training as a philosopher does not allow him to speak on where, exactly, our knowledge of cause and effect comes from. He seems troubled by this, but he has found a hole and cannot ignore it in good faith.

I appreciate this insight. It has led me to draw my own conclusions: that we are all in a constant mesh of cause-and-effect, and that our knowledge of this comes from our place in that mesh. That since we are effects already, we contain the seeds of more causes. One of those effects/causes is our ability to observe and learn from the world around us, to act on that knowledge in order to produce a deeper understanding-- and for functional purposes, we take the reactions we have observed before as the factual state of things going forward, even though this is not a belief founded in logic but in experience. Experience is a word which encompasses many things, including our capacity for logic, which is only a small part of a small part of the human mind. Human beings are a complex and highly self-conscious configuration of nature, and we tend to over-value pure reason, treat it as a tool with far more power than it really has. This work by Hume is the beginning of that realization. Would he agree with my phrasing? Would he be troubled by the spiritual life which informs my understanding of his work? Who knows, and who cares.

Demarcation and Demystification: Philosophy and its Limits - J. Moufawad-Paul

Here JMP defines, for himself and for the reader, his own philosophical project, by providing a definition of philosophical practice in general. His definition comes from a place which is critical of attempts at comprehensive metaphysical systems, and which sees philosophical practice as much more limited in scope than is often conceived. Essentially, to JMP, philosophy is the practice of interrogating and clarifying bodies of knowledge in order to "force meaning", ie. to make inconsistencies and gaps so clear that it becomes obvious which steps must be taken next. This being the case, philosophers often stray outside of their discipline, and people who are not philosophers often do philosophy spontaneously, whenever they try to make critical interventions within their fields.

His perspective is clearly informed by the fact that he is a philosopher of science, and he is attempting to understand his own role within the "theoretical terrain" of historical materialism. His story of how knowledge is produced goes something like this: people act within the world, and through action they produce bodies of knowledge that are always incomplete and often contradictory; philosophical intervention makes those gaps and inconsistencies clear; people take further action, which produces more knowledge, which fills in these gaps and can make these inconsistencies even more apparent; when the inconsistencies in a "terrain" reach an impasse, there are militant struggles between opposing camps who can make use of philosophical intervention in order to make the nature of the contradiction very clear. This has happened in the natural sciences many times, with the struggle for the theory of relativity (against Newtonian physics) a prominent example.

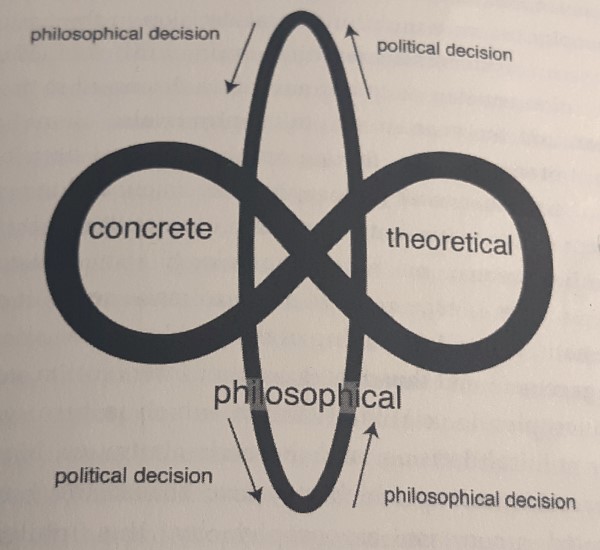

Through this account of knowledge production, JMP emphasizes that philosophical decisions are informed by political decisions, which are themselves informed by the bodies of knowledge that the philosopher draws from. And so he provides an outline for us to understand radical philosophical practice. The book has a great diagram to help visualize this process, although I wonder if it will make much sense out of context.

Now, what do I, someone who finds metaphysical speculation really interesting and valuable, make of this work? Honestly, I think it totally holds up, and I appreciate its critique. A philosopher of religion (or art, or any non-science) will do much of their practice in the same way that JMP describes, studying a body of knowledge, making political choices, and producing interventions. And we are better off if people who are doing spirituality, doing theology, etc. are open about that fact. It helps to keep it real, so that we don't create confusion between science and religion. Here I will link to another, short blog post where I get into my thoughts on that a little deeper.

"On the Concept of History" (aka. Theses on the Philosophy of History) - Walter Benjamin

Another read from the marxist internet archive. Aphoristic, spiritually informed historical materialism. A view of history which centers the series of catastrophic losses and failures that accompany every success, that sees mourning and honouring the dead as a vital historical task.

"Marxism and Historicism" - Fredric Jameson

Jameson details several ways of engaging with history, and their limitations. He then outlines a marxist method of encountering the past via the historical object, the primary source. When we read a text from a time and place which we have never visited, we are not absorbed into that setting, but we bring our present understandings to whatever we're reading. We bring our ideas about the setting from which the object emerged-- when I read Catullus, I start with my own ideas about what Rome was like two thousand years ago. But more importantly, we bring our current social conditioning, our own ideas about reality itself. At the same time, the text we're reading contains its own perspectives on reality, from its own context. As we read, these two worlds meet-- two modes of production, two cultures, two realities, two time periods, conversing with each other, judging each other, remarking upon gains and losses, similarities and differences. When observed carefully, we can see that happening all of the time, various pasts still alive in the present, sharing wisdom, passing judgement, haunting us. And maybe we can even sense the future's voice, and when we hear it we might call it the utopian impulse.

"Periodizing the 60s" - Fredric Jameson

Here Jameson links the decolonial Third World movements, and the instantiation of neo-colonialism, to the development of postmodern semiotic theory. This is my first time actually reading what Jameson has to say about postmodern academic theory, and it is tremendously helpful in untangling the knots that my bachelor's degree put in my brain. I am glad that I learned the basic introductions to postmodern and poststructuralist theories, but I wish they had been historically situated from the beginning instead of treated as decontextualized concepts. Historical materialism always helps to clear up these messes, and puts you in a better place to actually appreciate some of the more valuable contributions of these thinkers.

Letters to a Young Poet - Rainer Maria Rilke

I think this book is attractive to people who are starting to have spiritual awakenings, but who haven't found ways to put any of this wisdom into words. Rilke, or maybe the translator of this edition (Stephen Mitchell), or probably both, have a beautiful way of putting these things, although I think there can be a danger in putting too much value in the wisdom of words. I've heard plenty of 'wisdom' throughout my life, but it never really meant anything until I'd felt it myself. And now, reading these beautiful words, and recognizing clearly my own experience in them, it's a whole new level of not meaning all that much to me. But it was an enjoyable three hours of my life, and there was one passage that stuck out, because it contained my most recent spiritual revelation, one that I had thought was so private and idiosyncratic and uniquely mine. It is his passage concerning a belief in God, not as someone who was once real and has now been killed through lack of blind faith, but as a being that we are all in the process of building. "As bees gather honey, so we collect what is sweetest out of all things and build Him... we start Him whom we will not live to see".