1. Introduction / subjectivity check

When I was twelve, suffering under the realization that meat was produced by violent death, I tried to go vegetarian. But my knowledge of nutrition was poor, and I was dependent upon my dad's cooking anyway, so dinner was just meat-and-potatoes, hold the meat. Sometimes a veggie dog fresh from the microwave. We were buying and cooking as much meat as ever, my dad just got my share. Meanwhile, I started to lose hair, in big clumps. I lasted a few months before deciding that this protest helped no one. I confronted my powerlessness, a child standing before carnage on a massive scale, and gave up. But I never forgot what meat was. It was top of mind every time I ate.

Around this time, I started cutting. I was trying to acclimate myself to the violence of my world. If I couldn't stop industrial-scale slaughter, and if my body was too weak to survive without it, I could at least be penitent about it. In fact, maybe suffering could make me stronger. Mortification of the flesh and all that. And in light of my newly developing conscience, I was trying to find a safe venue for my rage. I was growing out of exorcising my violence by getting into fights on the schoolyard. I was the only acceptable victim I had left. I could turn my body into meat under my hands.

Then, meat-eating became a new perverse violence for me. Meat and leather and fur, a commodified violence, a socially acceptable evil. I knew the secret truth of these things and I couldn't forget it, I was embedded in it and I might as well get my kicks where I could.

This tension between conscience and need, lofty ideals and constricting reality, wanting to reject the world and wanting your vengeance, carried me into my twenties. In time, I learned how to cook. In time, I became "independent". Now, I have the resources and knowledge to go vegetarian. But I haven't. To be fair, I have oriented myself towards a mostly rice- and legumes- based diet. But my history, what I've already had to find ways to live with, prevents me from ruling meat out entirely. I've already rationalized and accepted so much.

I could say that I eat meat because my politics have changed. That I believe an animal-rights movement needs to be an ecological movement, an environmental justice movement, a worker's movement, rather than individualistic boycotts. That certain trends in the vegan movement are extremely hostile to Indigenous people and modes of living. That a sustainable future would probably include some meat consumption, some portion of the global population maintaining omnivorous diets. These are fair points, but they have nothing to do with my personal meat consumption.

The vegans aren't all wrong: industrial meat production isn't environmentally sound, and it's probably not ethical, either. These personal choices cannot be justified by way of sweeping political arguments. It's ridiculous and destructive to argue from the position of wanting your every action to be beyond reproach. And as a white settler, it would be extremely cowardly for me to appeal to Indigenous modes of living as an excuse to keep eating factory farmed meat. These are the kinds of things you see in the vicious arguments between vegans and omnivores online.

I'm not doing everything in my life in the most ethical way possible. I work to educate myself, to look right at the death that I sustain myself on, and as a long-term goal I'm trying to reduce my reliance on industrial meat production and all the abuse involved. I'm trying to ready myself for a world that will be transformed by climate catastrophe and the environmental justice movement. I don't want to be one of those crybullies on fox news whining that the libs are taking their goddamn hamburgers away. More than anything, I'm just trying to live my life in a way where I no longer feel so much guilt and self-directed-rage that I need to make myself bleed to cope. Admitting fault is part of that.

2. Stuffed (2019)

Stuffed is a 2019 documentary that profiles a handful of artists competing in the World Taxidermy Championships. There's something of a diversity of approaches, from naturalism to the fantastic, from hobbyists to people who work with museums to those who preserve hunting trophies. There is much that they share: their love for animals and nature, their comfort with death, their craft. A mesh of truths are highlighted throughout: that taxidermy allows people to come in close contact with nature, that it can be used to educate and forge meaningful connections, and that hunters, as a group, tend to be very knowledgeable about their local ecology and invested in conservation.

But there is an unspoken truth, a perspective that everyone in the documentary shares, which is never interrogated or commented upon: their whiteness. The artists are all white, most are anglo-american, one is a white south african, a couple are germans based in europe. The history of conservation in the USA is attributed to Teddy Roosevelt and his national parks, a white supremacist enacting a colonial project of land management. The white south african has a long speech about his connection to his land, his home, Africa. These aren't challenged in any way. Africans and Indigenous people of the Americas are hardly mentioned, let alone given time to speak for themselves. The shadow that settler colonialism casts over the film is much more disturbing than the taxidermy itself.

This contrasts heavily with the clean-cut, whitewashed, rose-tinted and romantic tone of Stuffed. This is a documentary that wants its subjects to be beyond reproach, it wants us to accept that they are just misunderstood artists and lovers of nature. This was a viewpoint I was more sympathetic to before watching the movie. Its refusal to engage with the ugliness of their perspectives is dishonest and disquieting. It feels like a cover-up and the end result is kind of nauseating.

I watched Stuffed because I am interested in taxidermy, as a potent interface between life and death. As is emphasized throughout the movie, the art of taxidermy is a study of life. Taxidermists want their sculptures to look alive. In order to do this, they have to study living animals, but they also become intimate with death, collecting dead animals in one way or another, dissecting them, tanning their skins and stitching them back together over frames of wire and styrofoam. This can be a beautiful thing, it can be an ethical thing, it can be a valuable art. The artists say again and again that they aren't necrophiliacs, that this is just their way of engaging with nature, and I believe them. Sort of. At least I don't think they're fucking the animals.

Stuffed spends a lot of time with museums, which have a long history with taxidermy. Like taxidermy, museums have the potential to be valuable. The production and sharing of knowledge are important in every human culture, and having some institutions devoted to these practices is inevitable. There should be places devoted to the study of art, culture, history, science, etc.

But there are people who have the power to determine what is studied, how knowledge is produced, and how people will be instructed to think. And the modern museum is rooted in an openly colonial, white supremacist, capitalist mission, so the frameworks it has developed have those characteristics and goals. The museum as it is currently constructed is a tool of colonialism. If a human culture is displayed in a museum, it is exoticized, locked-in-time, considered a thing of the past. The museum-going public, in contrast, is presumed to be white, modern subjects who can project their animus onto whoever we're anthropologizing today. Museums are also, famously, a way to showcase the spoils of conquest, with colonizing nations taking home trophies from their plundering expeditions, leaving the robbed nations to fight for the return of their treasures. Human remains are even put on display, within the same framework.

The museum, like taxidermy, then becomes an objectifying art of living death. In the settler mindset, so determined by the illusion of control over nature, and so enmeshed in a constant conquering violence, this is what love looks like. Appreciation is making a display of the dead. If an animal is driven to extinction, then at least we should have lifelike museum displays for the sake of the living to learn of this ancient thing now gone. In this way, the taxidermy diorama is even anti-conservationist, as it aims to safeguard the image of the most charismatic members of an ecosystem rather than protect the environment in which they could survive. Taxidermy is as necrophilic as the whole settler-colonial project, at least when practiced by unchallenged settler hands.

3. Bestiaire (2012)

Bestiaire is a 2012 documentary shot at the Parc Safari zoo in Hemingford, Québec. It is virtually dialogue-free, and mostly consists of long shots of the animals themselves. It is a chance to watch captive animals look bored, which is the real zoo experience most of the time. It took a long time before I realized that it was even shot in a zoo, however, because the film starts with behind-the-scenes footage that looks more like a slaughterhouse or industrial farm. No gore or death, but animals held in restraints while given medicine, or led down long metal hallways to an unknown destination. As the film goes on, the zoo displays and eventually the zoo-going public come into view. It's a pretty cool movie. I like looking at animals, and I like thinking about zoos.

Zoos were once mere collections of animals in small cages, tired and sad and not long for this world. (I'm sure some still are, though I haven't seen any that bleak). Carl Hagenbeck, born in 1884, in Hamburg, is considered the father of the modern zoo-- bar-less enclosures with micro-habitats similar to where the animals lived in the wild, where they are able to show some natural behaviour. Hagenbeck also always included a human component to his zoos. And I don't mean the guests. I mean enclosures meant to display supposedly savage people in their own micro-habitats, with shelters meant to be representative of the architecture of their respective cultures, and told to display behaviour 'authentic' to their culture. The idea was that the curious european public could learn a little about the people they were conquering, with the most important lesson being their own inherent superiority to these animalistic 'naturvolk'. It was a humiliating exploitation, and met with a lot of resistance. Many of the people used in human zoos were resistant to european opinions on what their cultures consisted of, fluent in the languages of the countries they were displayed in, and uninterested in playing along. Human beings are not displayed in zoos today because of that resistance.

Non-human animals are different from human beings. Most of them do not seem to understand precisely what humans are up to, and their methods of resistance are far less effective, when present at all. Since it's relatively easy for humans to communicate with each other, but communication is really difficult across species, it can even be hard to tell how some animals feel about their captivity. And some domesticated animals, whom we can communicate with rather well, seem comfortable with their conditions. Many captive and domesticated animals live healthy lives and show a healthy range of emotions. It's possible that some animals can participate in all of their natural behaviours while in a zoo, or while kept as a pet, as long as the zookeeper or pet owner is actually sensitive to what their needs are.

But even in the best cases, keeping animals in captivity is a philosophically and politically complex issue. It's worth bearing in mind that the modern zoo was born in the exact same instance as the "human zoo". The same mindset constructed both. And while the human zoo is a more obviously horrible thing, maybe this way of relating to non-human animals is kinda fucked up, too.

Why are we keeping so many animals in captivity, just for human pleasure? Yes, zoos are also used for study, but we know that the study of animals in captivity has serious limitations. Yes, zoos are used for conservation, with programs to breed animals who are endangered in the wild, but what is driving them to extinction in the first place? More than anything, the zoo is a way for human beings who are alienated from the natural world to look at animals. And pets are a way for people who don't have other non-human friends to form those crucial cross-species social bonds. These might be necessary practices right now, because they allow us to maintain a connection with the non-human world while so much is done to fracture that relationship. But we shouldn't get complacent. There have to be better ways, and they might not include keeping animals as captive property.

The future might still include forms of animal domestication. After all, we have been domesticating animals for far longer than we have had the modern practice of pet keeping and zoos. Any prolonged human engagement with a plant, animal, or environment seems to lead to its modification over time, sometimes to the point of domestication. Even the Amazon rainforest was partly engineered by humans, as the people indigenous to that area have lived there since before it was a rainforest. When human societies have their values in order, they can do amazing things in their ecological communities, foster diversity, live in constant learning, survive in unbelievably complex or harsh conditions, promote their own lives and the life all around them.

4. Hairat (2016)

Hairat is a short documentary shot on the outskirts of Harar, Ethiopia, and released in 2016. It can be watched for free here. It is the predecessor to director Jessica Beshir's beautiful feature length documentary Faya Dayi, also set in Harar, and which I touched on in my January-April film roundup here.

In Hairat, we meet Yussuf Mume Saleh, an older man who goes outside the walled city every night to feed meat to a group of local hyenas who have grown dependent upon humans for food. In a filmed interview published on the Criterion Channel, Beshir provides more context for what we see in the film. She explains that Saleh's nightly ritual is one of her old familiar memories from growing up in Harar, and it was one of her few constants as she returned to Harar throughout her life. She mentions that watching Saleh feed the hyenas is a fairly well-known activity, a thing to do, for many who grow up in Harar. The human desire to observe non-human animals, the same sort of thing that attracts people to zoos. She then goes on to provide some historical context:

"At some point, I think about a century ago, we had a famine. And when that happened, a lot of the hyenas were descending upon the city and attacking the cattle and, you know, sometimes even babies. So the elders got together to find a solution. And they came up with the idea that, well, the hyenas are hungry, too. Just as much as we're hungry, the hyenas are hungry, so we gotta feed them. So, every night, they would make a big porridge with a lot of butter. And right outside of the walled city, somebody would sit there and just feed them this porridge. So, the hyenas got used to that."

"Abba Yussuf has been feeding them for a long time. He knows the pack, and packs. He knows when the mother's here, he knows them by name. So, when you go there, you see his relationship with them and you realize that it's just so peaceful, and it's just so loving, and it's just contagious. You don't feel that fear."

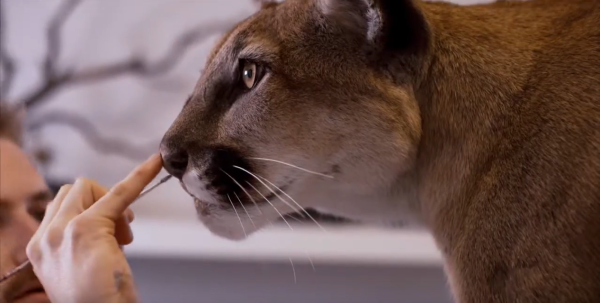

Hairat shows a different kind of human-animal relationship than we see in Stuffed or Bestiare. The hyenas are not domesticated, but they are somewhat acclimated to interacting with human beings, and through human choices the relationship has become less adversarial than it once was. The hyenas are not captives, and they are not objects. Saleh plays with the hyenas in a way that respects their nature, and makes his relationship to them clear. The choice that the elders made during the famine that Beshir talks about was to deescalate, rather than make war, and to compromise rather than subjugate the hyenas to their will. Their choices have had lasting consequences. It's not always ideal to have wildlife grow dependent upon human beings in this way, but in order to avoid needless bloodshed and to find a way to coexist with nature, this is a pretty beautiful example of people finding other ways.