Blasted in the Ass by Colonial Hogtown: a gamejam post-mortem

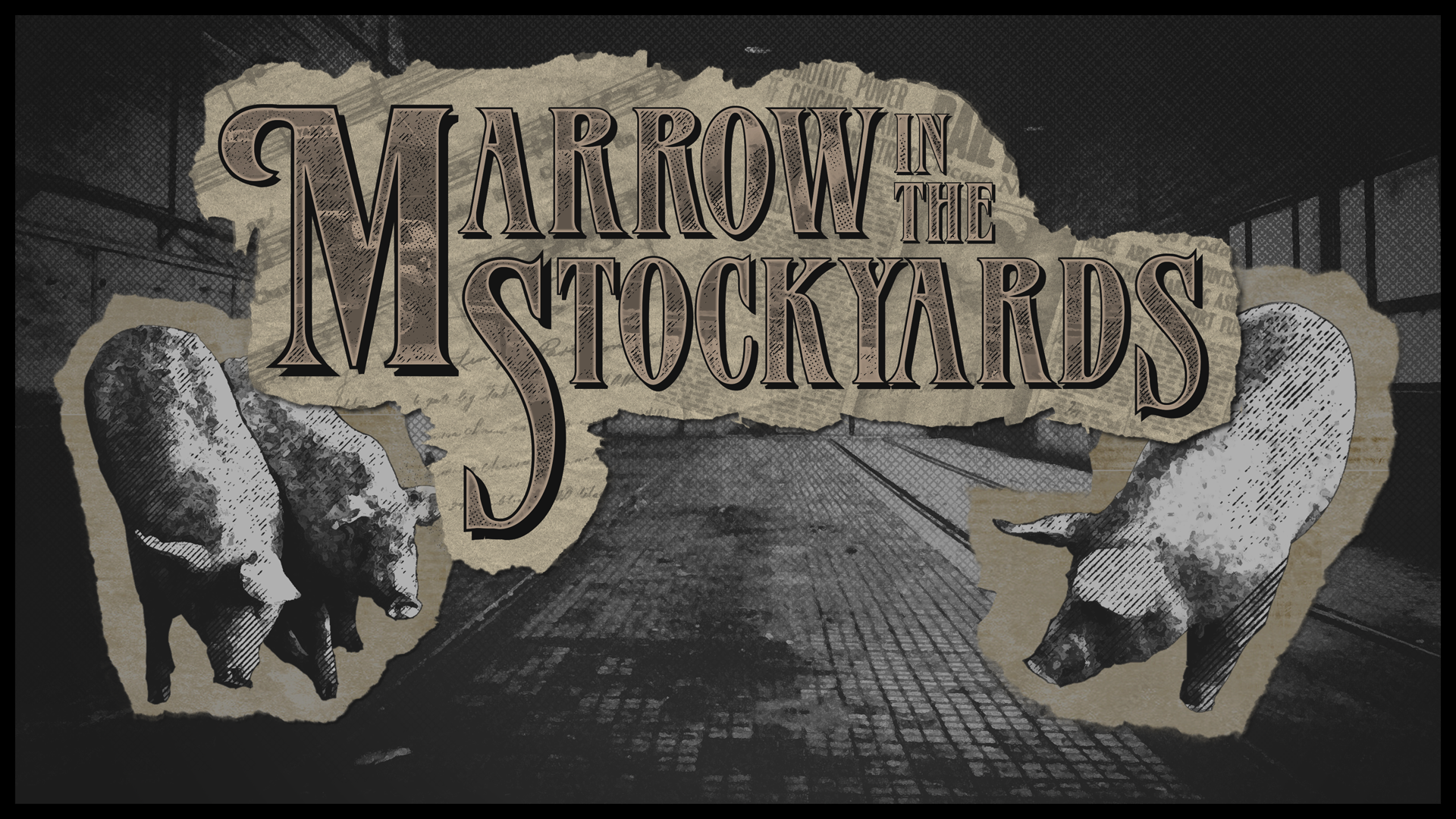

Toronto, 1928. Frostbitten and pious. Decay creeps just beneath the glittering splendour of the age. Work in a slaughterhouse and surrender to the atrophy of conscience, flesh, and reality itself. Download and play Marrow in the Stockyards now!

Do you love gore, blood, the roaring twenties, Victorian holdovers, guilt-driven madness, abortive class-consciousness, miserable husks, the death of innocents, the horrors of Tory Toronto, industrial-electronic jazz, gothic etchings, newsprint, collage, and visual novels that take approximately 30 minutes to play? What if I told you the game is both FREE and VERY GOOD?

I strongly suggest playing the game before you read on! It's available for windows, mac, and linux!!

Self-promotion aside, here's the postmortem.

The Team

When Quail invited me to write for a jam full of people I didn't really know, I was flattered, thrilled, and apprehensive. But I'm so glad I put my trust in them, because this could not have been a better experience.

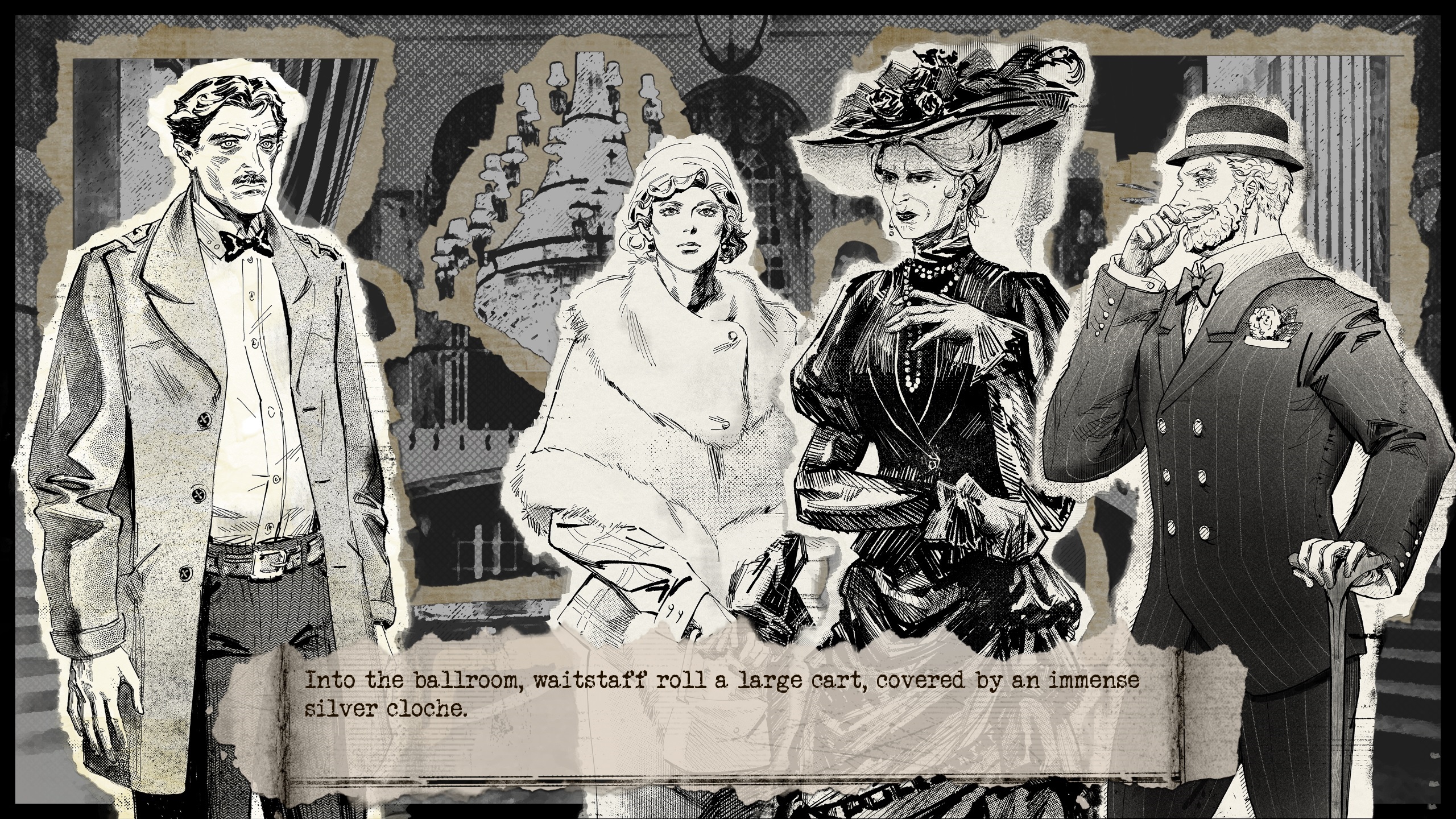

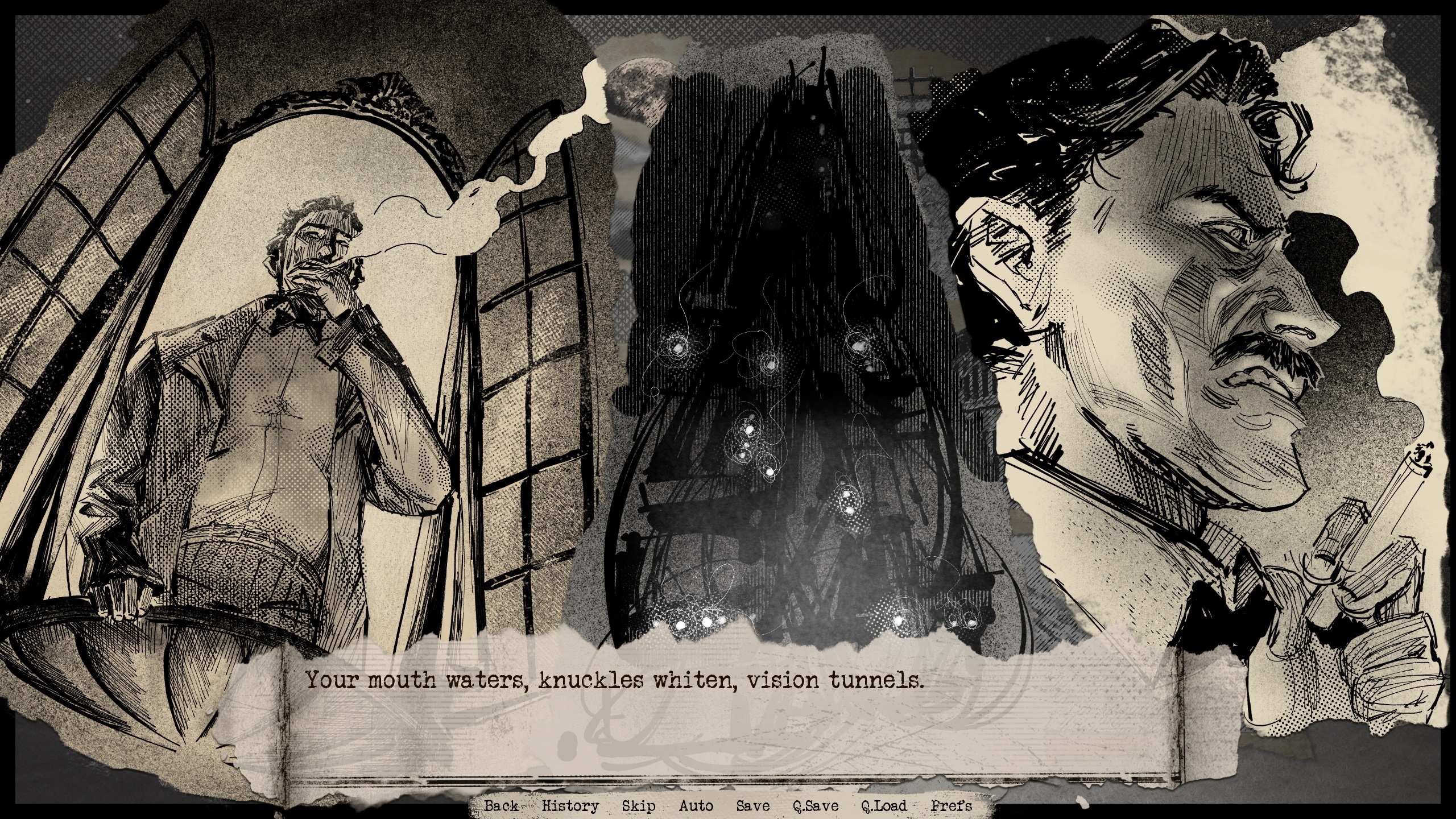

strateaux and iron_swan are absolutely phenomenal, visionary artists, and together they developed a look for this game which I couldn't have imagined in a thousand years. strateaux understood the characters so perfectly, it's like he could legitimately read my mind, and his art-- including his sense for animation and staging-- is fucking unreal. The UI is so tactile and evocative, it's like I can smell the paper. And iron_swan's background art is so immersive, with seemingly simple gestures creating such depth, demonstrating a tremendous talent for composition. Quail composed beautiful, wild, gnarly, creepy music, and put a sensitive ear to the sound design. Those wet, clickity-clackety sounds.... And oats is so professional, reliable, and fast, yet totally patient with troubleshooting our (my...) struggles to use computer. As a first-time gamedev with no coding experience beyond html text editing, I relied heavily on his help.

This was a uniquely driven, ambitious, compassionate, responsible, and talented group. I am beyond thankful that they went on this journey with me, giving up their weekends, bringing their boldest ideas, and, at times, sustaining psychic damage from the research. I strove constantly to get on their level. The project, and team, have been a genuine source of stability and inspiration in a nerve-shredding historic time.

The Process

Marrow in the Stockyards was made for NaNoRenO 2025, a visual novel game jam that runs every March. I pitched my premise to the team in February, and with their approval I started on my research right away. But any/all drafting, scripting, sketching, composing, and so on took place strictly within the month of March. We all agreed to give the equivalent of five weekends to the project, although there was some overbleed, and we ended up working a fair bit on evenings, too.

Simultaneous work might not be the most efficient workflow for a visual novel, but it offers some advantages. As a writer, it was uniquely inspiring to write the script while others filled in the rest. It's like a video game was being constructed around me while I wasn't looking. Whenever I paused to look around, usually at the end of a day, more incredible art had sprouted! Like magic, the game was suddenly playable! I had new tunes to listen to!

But simultaneity does have its complications. I tried to be very conscious of what my collaborators might need from me, and wanted my process to suit their needs as well as possible. First, I wrote a detailed, scene-by-scene outline, to try and help everyone get a sense of the setting, characters, and story we were working with. This also gave them a chance to voice any major structural concerns. Next, I drafted the first and last scenes. After that, I delivered a very rough draft of the remainder, so that we could finally all have something clear to work from. Subsequent work was on cleaning up the rough drafts, filling in any holes in the script. In the final week, I faced my fear of code, and I jumped into Renpy for final copy-editing and other last-minute fixes.

In an ideal world, it's probably more efficient for the writer to finish a rough draft before handing it off to the team. I was very conscious of the fact that when I diverged from the outline, added tertiary characters, changed locations, when a character reacted with different emotions than I'd first anticipated, I was throwing curveballs to the team. I tried to colour within the lines, and for the most part I did, but sometimes a scene really does need something you didn't expect. For their part, everyone on the team was very gracious and savvy, and we found ways to be efficient with our resources. If you only have five weekends to produce a video game, there are compromises that must be made. People will work more independently early on, and try to find ways to make their visions sing in harmony in the end.

Generally, we tended not to overthink. People would run their ideas by the team, get the go-ahead, and barrel forth. As we neared the end and playtested more critically, more ideas for improvements came forth, but these were usually non-controversial.

Then came time to pick a title, prompting the team's only serious debate. It's a choice that matters equally to everyone. Here's an incomplete list of optionss we considered: Flyblown, Blasted in the Ass by Colonial Hogtown, Marrow Deep, Marrow-bound, The Oracle's Marrow, The Marrowyards, M A R R O W, Stockyard Oracle, The Stick Pit Oracle, Fetid Oracle, Rended Flesh, Stockyard Abattoir, Rend and Reverie, Rend and Reap.

The debate lasted for days, but it was one of the healthiest I've seen. We'd warmed up to each other, learned to trust one another, and we'd all developed our own ideas about the project. People weren't afraid to raise their concerns, to share their own views, to say what words mean to them. Questions were raised, and people were interested in the answers. We treated each other with respect and dignity and good faith. Ultimately, while many of the above titles fell out of contention, we couldn't reach a unanimous deicison. An anonymous vote was put forth, and with that we found a title that everyone could be happy with. It was probably the least consequential, yet most satisfying experience of democracy I'd ever known-- perhaps a prelude to the 2025 Vancouver by-election, a process with promising results, but who knows what influence these ripples will have on the future, on broader society.

My Sources

- Randall White, Too Good to Be True: Toronto in the 1920s. Dundurn Press, Toronto, 1993.

- Tove Skaarup, Slaughterhouse cleaning and sanitation. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, 1985.

- Frank G. Ashbrook, Butchering, Processing and Preservation of Meat. Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, New York, 1955.

- Morley Callaghan, Strange Fugitive. 1928.

- Peter Kuper, Upton Sinclair's The Jungle. 2004 graphic adaptation of the 1906 novel.

- Workingman's Death. 2005 documentary film.

For a picture of Toronto in the 1920s, I looked at many library books, especially books of photography, but my favourite source was Randall White's Too Good to Be True, a slim, breezy, popular account of the time. It's not a deep work of scholarly history, it's just an entertaining portrait, but that served my purposes here much better than a rigorous work of historical materialism would've. It gave a pretty good picture of Toronto's culture at the time: the music, sports, religion, press, technology, arts, economy, cultural-linguistic communities. It was a very, very WASPy place, with a strong current of British loyalism and Toryism, and hardly anything you'd call a Canadian identity. It was described as the Belfast of North America. I was surprised to learn that at least a quarter of Torontonians at the time were actually born in the UK; over 80% traced their ancestry there (as opposed to about 40% today). Ernest Hemmingway and Emma Goldman both tried to live there, and hated it, accurately describing the city as stodgy, dull, bleak.

Too Good to Be True taught me about Blue Laws, about the end of Ontario's temperance movement, the developing auto industry, the fact that the "roaring twenties" hit Toronto quite late into the decade, and that the city didn't get wise to the Great Depression until two years after the great stock market crash. It was also my introduction to the Orange Lodge and Orangemen, an international British Protestant chauvinist organization which ran candidates in elections (and often won offices, including mayor), marched in provocative demonstrations against Catholics and non-whites, and enjoyed a pretty elite position in Toronto. Although the book admits that the likes of the KKK did try to establish themselves in Toronto, it seems that the Orange Lodge was Toronto's pre-eminent white supremacist organization, by far.

As both sides of my family are British settlers, and practically all of them lived in southern Ontario in this period, I did feel like I was getting a pretty clear picture of what the world of my great-grandparents was like. Even though my ancestors were more the suburban family farm type, not city-dwellers, and more like Amnesty International socialists, NDP voters as opposed to Tories, this stil gave me a pretty clear picture of their social context, the context for their mostly-tepid forms of leftism, their casual "apolitical" racism, the blandness of their tastes, their sleepy stiff misanthropy and tea and English gardens, their protestant agnosticism, their love of getting the hell away from Toronto.

Randall White mentioned Morley Callaghan's novel Strange Fugitive several times, until I started to get the idea that it might be important, and sought it out. Written and set in the 20s, in Toronto, I used it mostly to get a sense of the period's voice. But it was full of such baffling dialect that I couldn't really get a feel for it, and ended up using a pretty light touch with the slang. Still, it was a lively and intriguing portrait of the city.

One thing Too Good to Be True did not discuss was Toronto's meatpacking industry, but I knew that the slaughterhouses were an important part of the city's history. In fact, none of my library's books on Toronto really got into the meat industry, so I relied on the following online sources:

- This article from Old Time Trains, which seems to use the book The Stockyard Story by D.R. McDonald as its main source, and which provides some maps which really helped me picture the stockyards district. Bless the train fans for putting this up, big help.

- This article from the Canadian Encyclopedia.

- This weird article from Encyclopedia.com

- This article from the City of Toronto website.

While these articles gave me some sense of the big picture, none of them gave me a workable sense of the nitty-gritty of the industry, so I filled in those gaps with two technical manuals and one documentary. Slaughterhouse cleaning and Sanitation was produced in the 80s by the UN's Food and Agriculture Organization, and Butchering, Processing and Preservation of Meat was a guide from the 50s produced by the US government for the use of family farms and at-home butchers. Both of these give instruction in a vacuum, presuming ideal circumstances, but together they gave me a clear sense of an industry standard workflow and division of labour. These guides were balanced by the documentary Workingman's Death, which in its third act covers a meat-processing district in Nigeria, where approximately the same workflow is followed, but the conditions are far, far from ideal.

I also read Peter Kuper's graphic adaptation of Upton Sinclair's 1904 novel The Jungle, partly to get a sense of a slaughterhouse in a setting more like 1920s Toronto, and mostly just to check that I wasn't treading the exact same ground Sinclair had already covered in his most famous work. The Jungle follows a more classically tragic structure, whereas Marrow in the Stockyards is closer to cosmic horror, so I decided I was fine. I chose not to make my slaughterhouse as scandalously disgusting as Sinclair did in his, because the game takes place 25 years later, in a context where The Jungle itself had supposedly led to increased regulation. Besides, even a fairly clean meatpacking house is pretty disgusting, and I'm more interested in the dangers always come with capitalism, downsizing and the pressure to work faster, faster, faster, not the scandal of unhygienic practices per se. Sinclair has said that he meant for The Jungle to hit readers in the heart, but he accidentally hit them in the stomach. Well, I'm not quite aiming for the heart or the stomach, but for a particular spot in the mind. I doubt I'll ever know if I've hit it.

Other resources I found helpful include this chart of stats from the Toronto Maple Leafs 1928-29 season (thanks, sports nerds), the Online Etymology Dictionary, which I used almost compulsively to check my slang, Jane Eyre for the more Victorian dialect of the Barnes's, and wordhippo, always my best friend when I'm sweating bullets over diction.

Reflections

So, my main project for the past... three years... five years... is an overly-ambitious, high-concept debut novel, a novel which, I swear to fucking god, will actually be ready for beta readers soon. "Soon". (I've had Sraëka read many of the earlier drafts, but I'd let them read my mind if they wanted to). Novels are a lonely task, and the ultimate in delayed gratification. In some ways, a game jam is the exact opposite: collective work, on a short time scale, with a fixed deadline.

When I'm working on the novel (and I've been keeping up with it on weekdays), all I get at the end of the day is a head full of my own words, my own gripes with my words. It's not a pleasure to read my work back over. It's more like a compulsion. But with this team, at the end of the day, I got to see the awesome work they've done, and get a sweet hit of the true joy of art! I'd really like to get more of that in my life, in whatever medium. I have ideas for movies, theatre, comics, zines, the task is to find people who also want to make those things, and who can work well together. There are some ideas in the "talking" phase; we'll see what happens.

As much as writing the novel lacks excitement, there are things about that process which I do love. It lets me be an absolute control freak, without having to compromise or make room for anyone else's ideas-- total ego. It's helped me to get some ideas sorted out for myself. It's made me a better reader, better able to hold a long work in my mind. It's improved my memory, and my capacity for big-picture thought. My dreams have changed. My unconscious has changed.

The novel also helped prepare me for this project. I've developed a much better sense of how much I can feasibly write in one day. I also have a better idea of how long it takes to tell a given story, how many scenes it will need at minimum, a feel for how those scenes might be paced. I'm also necessarily more practiced in writing itself, and that may have done my prose some favours.

To allow myself a moment of self-critique, now that I've washed my hands of the project, Marrow in the Stockyards probably would have benefitted from more scenes focusing on the relationships between characters. Mary and Agnes's budding friendship, their ultra-conservative politics. Howard and Joseph's years together, Howard's feelings for him, a better sense of Joseph's life. These could have made Joseph's death more impactful, and laid a stronger basis for Howard's alienation. As-is, the story is pretty dense and subtle, and it asks a lot of the reader. There is not a lot of room to breathe, to feel, to reflect.

That said, I'm pretty happy with what I managed to achieve here. I learned a lot, about writing for VNs, working with a team, writing in historical dialect, learning how to code in Renpy (just barely, just enough to mimic oats's code, to implement basic changes without breaking anything). The end result is a fair enough story, a decent benchmark of my current abilities, and a statement I can stand behind. I don't need to write another slaughterhouse story, another 20th-century story, or another story about a miserable straight guy for a while. Onward we go.